Citizenship Records

Citizenship records held at the UW-Green Bay Archives can help you find facts about immigrants. To see which Wisconsin counties and years our citizenship records cover, check our local history and genealogy collections.

Local clerks of court were responsible for maintaining these records. They may exist either as original documents, filed separately or bound together, or as copies of the originals entered onto pre-printed forms in bound volumes. Additionally, they may be preserved in their original form, on microfilm, or in both formats. Citizenship records fall into five main categories:

Research Considerations

When searching for citizenship papers, keep in mind that individuals could file their first papers soon after arriving in the United States. However, there are many variables to consider. Your ancestor might not have filed for citizenship, may have delayed filing or may have only taken the first step without completing the process. Additionally, if they moved between filing the Declaration of Intention and the final Naturalization petition, their documents might be in different locations.

Declarations of Intention (First Papers)

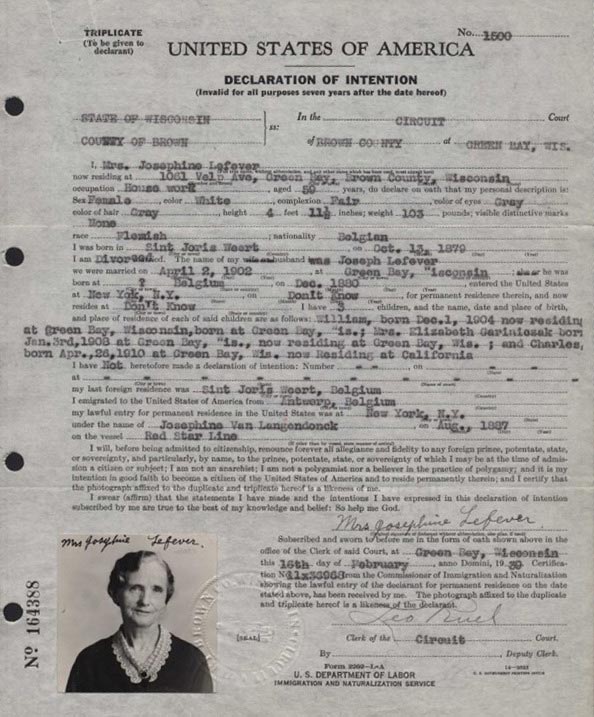

1940 naturalization application for Josephine LeFever in Brown County

Declarations of Intention, also known as first papers, document the first step in the naturalization process. In these documents, immigrants declared their intent to become U.S. citizens, support the Constitution and renounce their allegiance to their former country.

- Early Declarations (before 1906): Varied in format but typically included the immigrant's name, birthplace and date of arrival in the United States.

- Later Declarations (after 1906): Became more standardized, often including the immigrant's age, occupation, and physical description. Additional data like photographs, marital status and spouse's details were added in later years.

Petitions (Second Papers)

Petitions (sometimes identified as Petitions and Oaths, or Petitions and Records, or Naturalizations and commonly called second papers), document the second step in the naturalization process. After the required residency period, the applicant could petition the court for citizenship.

- Early Petitions (before 1906): Vary in content but always include the petitioner's name, oath of allegiance, date and witnesses' names. They may also include age, birthdate, port and date of entry and Declaration of Intention details.

- Later Petitions (after 1906): Became more standardized, with detailed information about the immigrant, their residence and their Declaration of Intention.

Naturalization Certificates

Naturalization Certificates were issued to newly naturalized citizens as proof of their citizenship status.

- Early Certificates: Vary in format and few courts retained copies. Surviving copies are often pre-printed forms in bound volumes.

- Later Certificates (after 1906): Became standardized, serially numbered certificates provided by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Local courts retained Certificate Stub Books with detailed information about the new citizen and their family.

Ancillary Documents

Ancillary documents are other records related to the naturalization process. These may include:

- Court Orders: Official court orders granting or denying citizenship. They list name, any change of name, and the petition number for each individual. The recommendations of the Immigration and Naturalization hearing officer were shown on the Naturalization Petitions Recommended to be Granted which may accompany the court order.

- Witness Testimonies: Two witnesses were required to attest to the residency and character of the petitioner. When the petitioner lived outside the state in which application was being made during part of the required period of residency, two additional witnesses from the place of previous residency were also required to testify. In these cases, naturalization examiners in other states were empowered to take written Interrogatories or Depositions of Witnesses from those additional witnesses. These are then submitted to the court as part of the petition.

- Repatriation Records: Under the Repatriation Act of 1934, any woman who had or who believed she had lost her citizenship (as a result of the enactment of the Married Woman’s Act) by virtue of her marriage to an alien prior to September 1922 and whose marriage with that alien had since terminated or who had lived continuously in the United States since her marriage was entitled to claim her citizenship by submission of the Application to Take Oath of Allegiance (also called Repatriation Record). The application listed her name, place of birth, date of marriage, spouse’s name and the date of the termination of her marriage or continuous residency. An oath of allegiance is also included.

Indexes

Indexes are tools that help researchers find specific citizenship records. They were created by clerks of court vary greatly from county to county.

- Types of Indexes: Card indexes (usually 3x5" cards), bound indexes (often with separate volumes for Declarations and Petitions) and indexes in the front of bound volumes of naturalization documents.

- Arrangement: Names are grouped alphabetically by the first letter and listed chronologically. Some indexes group names more closely but not completely alphabetically.

To address inconsistencies and omissions in some court-generated indexes, the UW-Green Bay Archives has created an online index for some of these documents. You can search these records by individual name using our records search and request.

Women & Citizenship

If you are tracing a female ancestor who arrived before 1922, it's best to trace them through male relatives. However, some women did file citizenship records prior to 1922, so it's still worth checking the indexes for their names.

Researchers using citizenship records will find relatively few early entries for women. From 1855 until the passage of the Married Woman's Act in 1922 citizenship was automatically conferred on the wife of any male citizen. Since then, women have been required to become citizens in their own right.

In Wisconsin, particularly in the nineteenth century, many more people filed Declarations of Intention than filed Petitions probably because the Wisconsin constitution granted the right to vote to anyone who had filed a Declaration. The state constitution was amended, effective December 1, 1908, to require full citizenship in order to vote.

Need More info?

Our citizenship records collection is extensive. If you have specific questions, we're here to help you find the answers.