Fish & Wildlife Habitats

A Wide Range of

habitats

The LGBFR AOC is ecologically diverse, but also susceptible to environmental change.

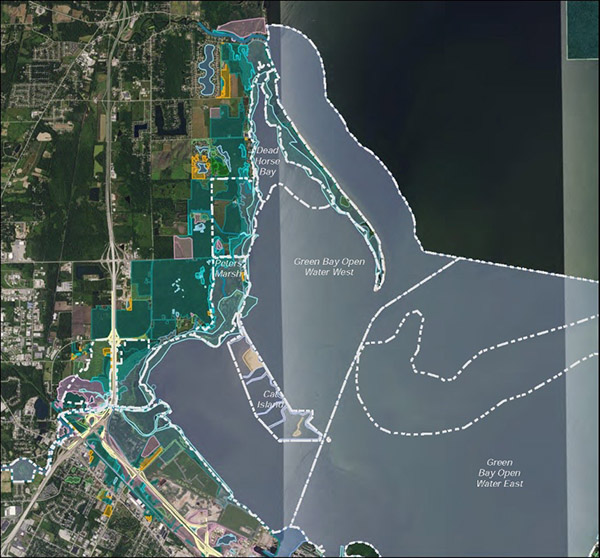

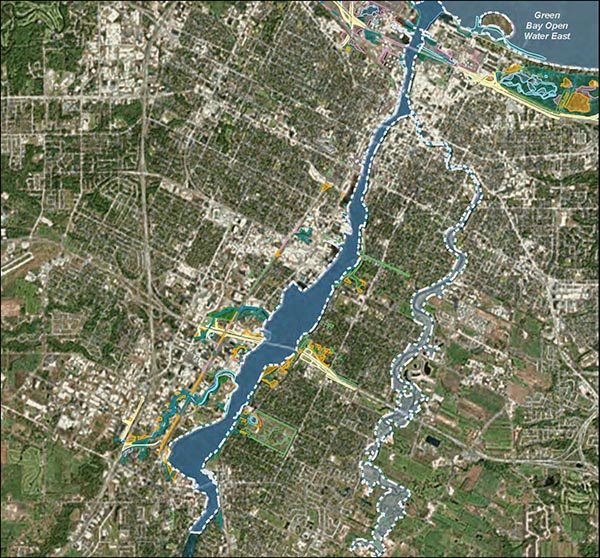

Our region features a range of habitats, from open water to emergent marsh to Great Lakes Beach, for wildlife populations to call home. The highly valued ecological diversity of these habitats is easily susceptible to habitat loss, pollution and invasive species. We've identified 18 priority habitats to enhance across the LGBFR AOC, as well as priority areas within the region.

Explore Priority Habitats

Though a lot of the area in the LGBFR AOC is agricultural or developed, a large part of it is open water as well as relatively undeveloped, semi-natural habitats.

Priority Areas

We've identified specific areas within the LGBFR AOC to address, including the Fox River and Cat Island.

Wetland

Wetland areas are important habitats for a wide array of animals, including species in decline like marsh birds.

Forest

Before European colonization, almost 84% of Wisconsin was covered by forests according to the DNR. Our work helps protect these forests.

Water

Open water is the most extensive habitat in the LGBFR AOC. As environmental challenges continue to affect the world, our water resources will continue to be indispensable.

Open

Open habitats, like Great Lakes beach, were once widespread in the LGBFR AOC, but today only represent a small portion of the area.

Assess our Habitats

Use a weighting system tool to determine the health of our area.

The UW-Green Bay project team established a weighting system in order to identify those priority habitats that are most critical to and would have the largest impact on the LGBFR AOC if improved in terms of quality (e.g., restoration or enhancement project). Using this weighting system and the newly assessed conditions of each priority habitat, the tool then calculates a weighted average score ranging from 0 (maximally degraded) to 10 (minimally degraded) that describes the “health” or “ecological condition” of fish and wildlife habitats in the LGBFR AOC (i.e., the “loss of fish and wildlife habitat” BUI). Improvements made to priority habitats with higher weights will have a greater impact on overall condition.

Maps

Find each habitat type within the Lower Green Bay and Fox River Area of Concern. Interactive GIS Map

Ask an Expert

As a proud alumna of UW-Green Bay, Erin Giese understands the need to provide hands-on experiences for students. She's committed to training the next generation of scientists who help to improve the LGBFR AOC. If you have questions, she can help!