Chapter One: 1969–1970

"I remember driving down the highway, looking back at those buildings, and I couldn't imagine how anything would be ready in time. There was so much to be done, and I was leaving on vacation. But it happened. I don't know how, but when I came back the furniture was in and classes had started. I had left half-empty buildings and come back to a university in session, alive and bustling."

-Marjorie Conway Fermanich, secretary and administrative assistant to the chancellor, 1967-1987

It was Friday of Labor Day weekend, 1969—four days before classes would open on the new campus. John Shier remembers it well. He was one of a dozen or so members of the faculty and staff who answered an urgent call for help moving in—any kind of help, day or night—from Chancellor Edward Weidner. Shier was assigned to a crew in the Laboratory Sciences Building.

“We hauled in desks and chairs, tons of them, from cartons piled in the halls, and moved them into their rooms under the eye of someone who told us where everything should go. It was a panic—classes were about to start, and here we were. Outside, raw earth everywhere; inside, offices with holes in the walls and wires sticking out where computers would be installed someday. Nobody was thinking then of personal computers all over the campus.

“Everything smelled so incredibly new. I remember thinking, someday this furniture will be worn from use, and in 20 years the trees will be grown and the campus filled out. After the Deckner Avenue building, it seemed unbelievable that this would be our home. There was some sadness, too, at leaving the old, friendly quarters behind.”

For Donna Scheller, student government president, it was an exhilarating time, that first day on the new campus and the months that followed. From a pair of tables in the lobby of one of the buildings, she was operating the University's first information center, which she had created and organized for a grateful administration.

“We were able to locate almost everyone,” she recalled. When people came by to ask the location of this classroom or that faculty member's office, we had it. We figured it was a feather in our cap when the switchboard called because they couldn't locate a room or a phone number, and we were able to supply the information.”

The University opened with three buildings, imposing in scale but dwarfed by the barren, 600-acre site of hay fields and pasture. Only the Environmental Sciences and Laboratory Sciences structures were visible; the single-story Instructional Services Building, housing the library, data processing center, audio-visual production facilities and bookstore, lay beneath an unfinished plaza. Academic deans had moved in from a cottage on the bay shore; a few members of the student services staff occupied offices on the new campus, while others remained at the UW Center on Deckner Avenue.

Chancellor Weidner and a small staff worked in a farmhouse off Bay Settlement Road, while university business operations proceeded from another farmhouse a mile away. In a bay shore cottage vacated by the deans, the news and publications office shared quarters with a duplicating shop installed on an enclosed porch with a magnificent view of the bay.

University Business Office

Students traveled by shuttle bus between classes on the campus and at the Deckner Avenue building five miles into town, where the freshman-sophomore center had been located for almost a decade. Spaces at Deckner, which would continue in use for three more years, included the gymnasium, for basketball practice as well as other sports and recreation; a modest music-drama room and a cafeteria-lounge; faculty and staff offices and a large lecture hall.

The 2,000 students on hand as the academic year began competed with faculty members for 580 spaces in the parking lot. They stood in line at lunch time, when a limited menu was offered at the Deckner cafeteria, seating 200, at a 120-seat snack bar on the new campus, or at the clubhouse on the Shorewood golf course, recently acquired as a future building site.

The opening of the campus was accomplished just a year after UW-Green Bay had officially taken control of the Green Bay Center and of three satellite” campuses in Northeastern Wisconsin.

The opening of the campus was accomplished just a year after UW-Green Bay had officially taken control of the Green Bay Center and of three satellite” campuses in Northeastern Wisconsin.

Deckner Avenue building

Under a master plan developed by the state's Coordinating Council for Higher Education, freshman-sophomore units at Manitowoc, Marinette and Menasha were now integrated administratively with the University in Green Bay. A Center dean at each location continued to oversee day-to-day operations, but now reported to Weidner rather than the chancellor of the Center System. All three centers, envisioned as feeder” campuses for Green Bay, were revising their curricula to facilitate transfers to Green Bay for the junior and senior years. Altogether at the four locations, as the fall semester began, some 3,400 students were enrolled from 48 of the state's 72 counties. They had come from as far west as Chippewa Falls, from Florence County to the north and Milwaukee County to the south. At Green Bay, along with students who commuted from homes nearby, 200 men and women from out of town were living off campus in apartments and private homes.

The opening of the campus was accomplished just a year after UW-Green Bay had officially taken control of the Green Bay Center and of three satellite” campuses in Northeastern Wisconsin.

Under a master plan developed by the state's Coordinating Council for Higher Education, freshman-sophomore units at Manitowoc, Marinette and Menasha were now integrated administratively with the University in Green Bay. A Center dean at each location continued to oversee day-to-day operations, but now reported to Weidner rather than the chancellor of the Center System. All three centers, envisioned as feeder” campuses for Green Bay, were revising their curricula to facilitate transfers to Green Bay for the junior and senior years. Altogether at the four locations, as the fall semester began, some 3,400 students were enrolled from 48 of the state's 72 counties. They had come from as far west as Chippewa Falls, from Florence County to the north and Milwaukee County to the south. At Green Bay, along with students who commuted from homes nearby, 200 men and women from out of town were living off campus in apartments and private homes.

Some had been attracted by an academic plan already winning national attention for its innovations. Chancellor Weidner, in his first address to the Green Bay faculty, described the plan as the type of approach to higher education that is long overdue,” but cautioned that we have things mostly on paper at this point.” Weidner went on to review the key elements of a UW-Green Bay education: a focus on ecology, the man and environment relationship; integration of disciplines into interdisciplinary concentrations” offered through four theme colleges and a school of professional studies; a four-year sequence of liberal education seminars, required of all students; a 4-1-4 academic year calendar—two semesters separated by a special studies” period in January; and a close relationship between university and community.

“I think the only way we can do something about the world is to assume that we are not all the people,” Weidner declared in an early address on the academic plan.Indeed, those of us in higher education are only a very small minority, and not representative of society. We must then go ahead and meet with our brethren on equal terms in a cooperative attitude, bring the community into the campus and the campus into the community...through all our activities including classroom teaching, including research, including curriculum building.”

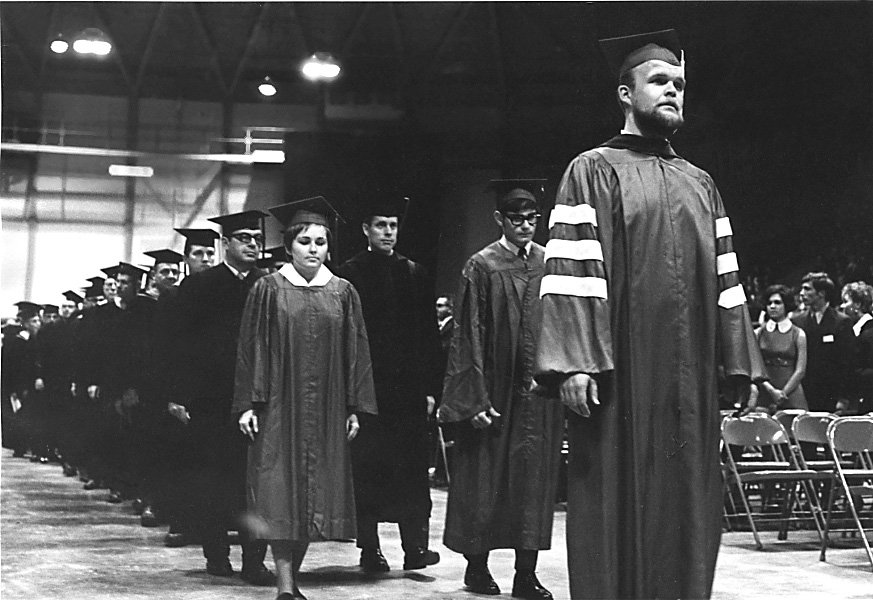

Year One of the University was marked with a public celebration on the second Thursday in October. At an evening convocation at Brown County Veterans Memorial Arena, representatives of 50 colleges and universities marched with faculty and staff in a robed procession to the music of the Green Bay Symphony Orchestra. Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins was the principal speaker. He saluted the fledgling University for its readiness to take on the essential challenge of our time: to see our world as a whole, to see the great big blue ball...to recognize that the educated man in our time cannot truly consider himself educated unless he understands what happens on the rim of the wheel, unless he understands what is required to make this planet safe and fit for human habitation.”

The community was invited to the convocation. Government officials, legislators, local business leaders and academics responded with enthusiasm. The general populace of Green Bay—whose children would be served by the University—stayed away, for the most part. Of far greater interest to the local citizens were the campus tours offered earlier on the day of the convocation and over the weekend that followed. Families trooped through the still-unfinished interiors, trying out multicolored classroom chairs, examining laboratory equipment, and pausing in the Environmental Sciences Building auditorium to listen to the University's first concert band.

During the months that followed, Chancellor Weidner sounded the call to communiversity” over and over again. He spoke to chambers of commerce, service clubs, legislators and government officials. He consulted regularly with 15 community advisory committees, which by now included about 200 individuals from all over the region. He opened his home to meetings of student government officers and a student advisory board. And he prodded faculty members not only to share their expertise in community projects, but also to invite business and professional people into their classrooms as lecturers.

A community appreciation dinner hosted by the University in December proved another successful effort to mingle town and gown.

Hundreds of community leaders of Northeastern Wisconsin attended the affair to applaud the achievements of the first few months. In place were furniture, books, and sod, cut from the golf course. The fall had seen a first foray into intercollegiate competition by University soccer and basketball teams, the debut concert of a band and choir, the expansion of performance and lecture programs both at Green Bay and at the two-year centers, and the birth of The Fourth Estate, a weekly newspaper produced by and for students at all four campuses. A United Student Government, with representatives from each campus, was taking an active role in decisions affecting student life and the academic program. And new faculty members and administrators were arriving from Hawaii, California, New York, Florida and Canada.

The University was now a fact of life in the Northeastern Wisconsin community. But those who hailed its promise continued to be outnumbered by others who perceived its presence as an unwelcome instrument of change, to judge from a study made public just five months after classes started on the new campus.

“The University of Wisconsin-Green Bay has tried—maybe harder than any other university—to involve the community in every aspect of its planning and operation,” wrote Green Bay Press-Gazette reporter Carolyn Stewart.But the results of a survey of 750 Green Bay area persons indicate that the University has not gained the respect and support of a significant proportion of the general public.”

According to the study, carried out as a student project through a questionnaire carried door to door, 53 percent of the respondents harbored basically negative attitudes toward the school; 36 percent registered positive responses, while 11 percent gave no indication of their attitude. Local residents indicated that they were more fearful of trouble” than anything else: marches, anti-war demonstrations, mobs, militant radicals, drugs, partying, disrespect for law and dirty art.”

“Whatever they called it, the respondents...seemed to be reacting to a vague impression of the turmoil on a number of campuses throughout the nation rather than to the real school in their own backyard,” Stewart commented. During the fall semester UW-Green Bay students had, indeed, taken part in peaceful marches coordinated with Vietnam war protests conducted nationwide. One or two students had been arrested and charged with possession of marijuana, but the charges had been dropped. Otherwise, none of the anticipated evils had thus far come to the campus.

Accepted or not by local folk, the fledgling University was already making its mark in the academic world and beyond. In November, three months into the University's first year, the Chronicle of Higher Education featured UW-Green Bay on its front page with a 1,200-word article by staff writer Malcolm Scully. The piece was accompanied by four photographs and headlined Environmental Problems Will Be the Central Concern of New University of Wisconsin at Green Bay.” A week later, in a piece that identified saving the environment as the new super cause of American youth,” a national Associated Press story identified UW-Green Bay as organized entirely around man and environmental problems in a new and radical academic experiment.” As the year ended, Harper's John Fischer provided a warm holiday salute” to UW-Green Bay as one of four colleges experimenting with the principles of Survival U.—offering an education which might, just possibly, save the human race from wiping itself out by overpopulation, war and the destruction of the environment.” (Two years later, Fischer would devote an entireEasy Chair” feature to the University, with far-reaching consequences for the UW-Green Bay image.) And Innovation magazine's quarterly issue, also appearing in December, pointed enthusiastically to the Green Bay concept as probably the most significant innovation in higher education in the United States in the 1960s.”

The acclaim would continue as one national publication after another—from Seventeen to Science —announced its discovery” of UW-Green Bay, all too often in stories that focused on a narrow definition of environment.” In the mood of the moment, the oversimplification was understandable. U.S. Sen. Gaylord Nelson's call in January 1970 for an environmental teach-in struck a responsive chord on campuses and in communities across the country. President Richard Nixon underlined the escalation of ecological concerns when, in his State of the Union message, he observed,The great question of the '70s is: Shall we surrender to our surroundings, or shall we make peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?”

Amid the glow of national recognition and growing visibility in its own community, the University plunged ahead with astonishing speed in the development of programs and physical plant.

Before fall semester classes adjourned, Lovell Ives of the music faculty presided over the public debut of the UW-Green Bay Jazz Ensemble and Pop Singers before a capacity crowd in the Deckner music-drama room. Early in January, 150 juniors and seniors departed for the first overseas study program in London. In the same month, ground was broken for an eight-story library to house collections which had grown in a year from 15,000 to 60,000 books and 200 to 2,000 periodicals. And before the end of February another groundbreaking signaled the beginning of construction of the first student housing: nine two-story apartment buildings for 567 residents. A private developer, Public Facilities Associates, would build, own and operate the complex on a 40-acre site adjacent to the campus. The apartments would be ready to occupy by the beginning of the 1970-71 academic year.Now it really will be a university,” declared Nancy Jochman, a sophomore who spoke at the groundbreaking.

After a controversy over the cost of locating a heating and chilling plant across Highway 54-57 from the campus, the State Building Commission approved funds for a $4.7 million utility structure to replace a temporary building. In mid-January community residents joined students and faculty members for an open house at a human development center, established on the campus as a nursery school and observation center for students in the human development program. With quarters in a remodeled house, the center opened in February to 15 three- and four-year-olds whose parents were members of the University community.

The spring brought re-opening of the Shorewood golf course as a nine-hole layout open to the public. And on April 22 the University joined colleges and universities all over the country in celebrating the first Earth Day. The day's events would climax several months of activities to foster environmental awareness.

University students and faculty joined local clergy, paper company officials, labor leaders, public school teachers and members of conservation groups in a county-wide committee to plan the observance. Schoolroom sing-alongs of environmental songs, poster contests and slide shows echoed theSurvival '70s” theme adopted by the committee. On Earth Day itself, morning-to-evening lectures and discussions on all four UW-Green Bay campuses targeted the main program: an evening extravaganza at the Brown County Arena featuring Victor Yannacone, an attorney and activist on environmental issues, and M. King Hubbert of the U.S. Geological Survey. While Hubbert delivered a scholarly appraisal of the bleak future of fossil fuel resources around the globe, 50-mile-an-hour winds and hail tore at the arena roof, demolished windows in the motel next door, and uprooted power lines. The storm and the survival” of the 3,000-member audience got top billing over the speeches in next day's Press-Gazette account.

If environment was the “new” cause on campus, the old” one—the Vietnam War—erupted tragically into the foreground in March 1970 with the shooting deaths of four Kent State University students in a clash with the Ohio National Guard. Two days after the incident, 500 students from UW-Green Bay, St. Norbert College and two Green Bay high schools rallied in protest at the Federal Building, moved on to City Hall, and hoisted a peace flag on the City Hall flagpole. The flag would remain, Mayor Donald Tilleman promised,as long as there is peaceful dissent in Green Bay.” Then the mayor joined the students in their march through the downtown streets. Thursday, March 7, was declared a day of mourning; the night before, 2,000 collegians and local citizens walked in a silent, candle-lit procession from the Deckner Building to downtown.

Kent State protest march

Year One events continued through the spring semester at all four campuses, reminding residents of each community of the new status of their local institution of higher education.

Nationally prominent dance companies, chamber music ensembles, theater groups and lecturers entertained audiences at the four campuses. Green Bay faculty and administrators spent in-residence days at the two-year centers, explaining the UW-Green Bay curriculum. In student voting for an official campus mascot,Phoenix” won the day over such entries as Hydros, Mavericks, Beavers, Voyageurs and the two runner-up choices, Nicolets and Loggers. And the admissions office announced that tuition for the 1970-71 academic year would be $450 for Wisconsin residents. A student living at home could expect to pay an additional $100 for books and supplies and $500 for transportation and miscellaneous expenses, counselors estimated.

Chancellor Weidner fielded questions about the University as host of a call-in series on a Green Bay radio station. During a second open house program on the campus above the bay, parents and townspeople checked on the progress of the student apartments under construction, toured the nursery school, the ecumenical campus ministry center—just opened in a residence above Nicolet Drive—and the golf course clubhouse, spruced up for use as a student activity center.

Kent State protest march

The University's first commencement, on June 1, 1970, was planned as an outdoor ceremony. According to plan, graduates would be escorted by faculty members, one at a time, up the steps of the concrete plaza, under blue skies, with flags waving in the breeze above them. Rain and wind chased the celebration into the Deckner gymnasium. Nancy Ably of Green Bay was the first to cross the platform and receive a diploma from Chancellor Weidner. The class was predictably mature: Helen Glickman, at 47, was the oldest of the 78 seniors, all of whom had completed most of their undergraduate education elsewhere. One-third of the group were aged 30 or older, and half were married. Green Bay residents numbered 53 of the total; the rest came from communities within a 75-mile radius.

As commencement speaker, New York Times columnist Max Lerner spoke on the theme “Angles of Vision.” Gov. Warren Knowles saluted the University as an institution representing a new wave of educational thought” at a school destined to become a truly great university” as it offered an education tuned in to social concerns.” President Fred Harvey Harrington of the UW System delivered the charge of responsibility to the graduates; Dr. James Nellen brought greetings as president of the UW Board of Regents. And in establishing a tradition of honoring members of the Green Bay community for their contributions to the campus, Weidner presented the first Chancellor's Award of Merit to Rudy Small, vice president of Paper Machine Converting Company, and John M. Rose, president of Kellogg Bank.