Chapter Ten: 1976—1977

“I know that our enrollment is going to decline this year compared to last. Yet this morning I feel optimistic, cheerful, happy and convinced that we have a remarkable institution with a remarkable future.” - Chancellor Edward Weidner, Sept. 11, 1976

Weidner launched his annual breakfast message to the assembled faculty and staff with typically up-beat words and a demeanor to match. And if one could ignore the enrollment picture, a review of University activities during the nation's 200th anniversary year offered reasons to celebrate.

There were, first, the public events saluting the Bicentennial itself: concerts of American music by the bands, campus choral ensembles and the Green Bay Community Chorus; performances of The White House, a reader's theater play providing intimate glimpses of presidents and their wives through history; and an exhibit of folk art, wooden ducks to patchwork quilts, produced by area residents. Three women—members of a Women: Myth and Identity course—exhibited a hooded cradle, table and corner cupboard in Shaker design. They had built the pieces almost entirely with tools available in the 1700s.

The American Heritage Ensemble, a professional troupe based at the University, took its tuneful new show to the far corners of the state. And If Elected... played before hundreds of high school students during the academic year. Several thousand more adults and children cheered the musical documentary of campaign hoopla at performances in Wisconsin state parks throughout the summer.

In June, with support from a Bicentennial Commission grant, faculty-student teams set out to explore farmsteads in three nearby counties, seeking architectural evidence—distinctive brickwork, arches and gables—of early Belgian settlements. By August they had visited 150 homesteads, gathering a wealth of photographs and descriptions for the University library's new Belgian-American ethnic heritage collection. In October curator Dorothy Heinrich presided over a public open house marking the official opening of the collection of family histories, pictures, maps, and village and church records from the days of the earliest immigrants to the region.

Michael Raye and Craig Konowalski, members of the American Heritage Ensemble

Thousands of visitors came to the campus for other events and activities during the Bicentennial year:

- An environmental workshop, focused on land use, for high school teachers and students;

- A Saturday session on building and flying kites for “kids of all ages”;

- A statewide Explorer career conference for 800 Boy Scouts on the theme “Tomorrow Is Now,” and a separate career education workshop for high school principals;

- An outreach office Day on Campus, offering tours, library visits and swimming along with mini-courses and workshops on subjects from camping know-how to Old Testament literature;

- The third annual Wisconsin Women in the Arts Conference, featuring artist Judy Chicago and author Kate Millett;

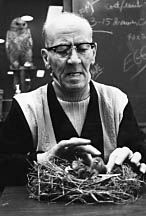

- Dedication of the natural history collection presented to the University by Carl Richter, an ornithologist living in Oconto;

- Puppet shows, recitals, gallery talks, demonstrations and films presented without charge in the daytime Concourse University series.

It was also a year of “firsts”:

- The first parents day planned by the Office of Admissions;

- The opening to the public of Bayshore Outing Center docking facilities and outfitting shop;

- The first international dinner prepared and served by students from overseas, with a menu centered on African stew;

- Broadcast over 14 weeks of “Understanding Presidential Elections,” taught by Forrest Armstrong of the faculty as the first credit course offered statewide by radio from UW-Green Bay;

- Establishment by the Founders Association, now at 117 members, of a new scholarship program recognizing leadership and academic excellence;

- Installation in the library of a new electronic security system, designed to curb losses of more than $11,000 in materials every year;

- The first major grant to the graduate program—$160,000 from the National Science Foundation, for use over 38 months to build and staff a resource recovery experiment station for the solid waste management program.

Ornithologist Carl Richter, donor of bird eggs and nests to the University

At spring commencement, Rob Stevens, a growth and development major, received the first outstanding student award for taking “a major role in reviving interest in student government.” As chairman of the Student Union Steering Committee, Stevens worked with leaders of the Segregated University Fee Allocation Committee (SUFAC) to write and win approval for a constitution uniting the two groups in a new Student Government Association. The previous organization, dating from two-year center days, had dissolved in 1972.

Newly energized student activists all but ignored the 1976 Earth Day, which came in the middle of spring break. But at least a hundred joined 91 faculty members and a few dozen farmers in protesting the construction of a new interstate highway and high-level bridge near the campus. In a letter to Gov. Lucey they urged a moratorium on I-43 construction until state officials could restudy the plan and find an alternative. Completing the 67 miles between Sheboygan and Green Bay would cut many farms in two and bury 2,000 acres of productive land under the roadway, the protesters said. UW-Green Bay administrators argued on the opposite side: The highway and Tower Drive bridge were crucial to providing access to the campus for students outside the immediate area, they said.

Ed and Jean Weidner preside over one of the early Founders Association receptions.

As Weidner prepared to address his colleagues at the beginning of the 1976-77 academic year, however, he was intent on looking ahead instead of backward. And the chief object of his scrutiny was the Logan-Murphy report. Under “15 significant points” Weidner provided a preview of the document embellished by a list of his own priorities: earlier decisions by undeclared majors, evening office hours to accommodate evening students, experiments with Saturday classes, a review of credit-by-examination procedures, and implementation of associate degree and extended degree programs. Echoing a major point of the report, he declared: “We should start with new students where they are and not where we would like them to be.” That requires some “re-analysis” of freshman and new-student programming, he admitted. But he made no mention of the most controversial Logan-Murphy recommendation: to eliminate requirement of the liberal education seminars. The problems of enrollment and retention were linked not to the academic plan but to perception of that plan, he said.

“We are perceived at best as ... turning out a series of bio-physical specialists. We are perceived at worst as being a very impractical and theoretical institution. The whole genius of our plan is 100 percent different from those perceptions.” Besides, Weidner argued, the enrollment shortfall of the past two years was largely in freshmen from Brown County—the area of the state with the highest proportion of high school graduates who had no plans for post-secondary education. “I think we have the right academic plan for the marketplace,” Weidner affirmed. “The only thing that is wrong is the perception of that plan. We must change the perception.”

Weidner reminded his audience that he had not originated his 15 points of emphasis. “They were developed by faculty and staff in official reports and reactions to them. Implementing these will not take major new time and input from faculty members,” he said.

The catalog of “primary goals” for the new academic year ended with an assignment Weidner took as his own: to work for student housing on the campus.

Just two months later, in November, the regents endorsed a UW-Green Bay proposal for dormitories. The initial project would consist of four two-story buildings, each housing 200 students. No tax funds would be sought; two-thirds of the $1.55 million cost would be paid by private donations and one-third by self-amortizing funds from rental fees. Student rents would also pay annual operating costs. The project already had the backing of UW President John Weaver, according to Weidner, who expressed cautious optimism about the hurdles ahead in the State Building Commission and the Legislature.

“I think we can get approval in the long run,” he commented. “Whether we will at this time, I can't tell. We hope to at least achieve an understanding of our need. ... I think the key consideration is that we have a statewide mission designated by the regents. We are not a regional campus. We cannot be a statewide campus without dormitories.”

The state's Department of Administration killed the project the following February and deleted the UW-Green Bay request for $1.55 million in up-front funds from the UW System building budget for 1977-79.

The UW-Green Bay numbers were too optimistic, the Building Commission argued. An estimate of $25 per square foot for construction was too low. Higher rental rates than those projected—perhaps unacceptably steep for students—would have to make up the difference. After the Legislature refused to reverse the DOA decision, and Lucey publicly challenged the wisdom of building dormitories at a University where enrollment was declining, the project was shelved. Campus planners would be obliged to wait for the 1979-81 budgeting period before they could again seek approval for student housing.

Faculty members, meanwhile, struggled with Weidner's admonition to “start with new students where they are,” particularly in regard to the liberal education requirement for graduation.

The original 24-credit, four-year series of liberal education seminars had already undergone a number of revisions. They included a new name, University Seminars Program (USP), and a reduction to 18 credits: six during the freshman year, nine in the intermediate years (sophomore and junior) and a three-credit senior seminar. But the initial concept was largely intact.

The freshman segment, in particular, had drawn the fire of critics. Four seven-week modules for first-year students centered on “an introduction to the two central concerns of the University: values and the environment.” In groups of up to 35, the students pursued assignments of critical reading, writing and discussion on such topics as the human condition in world perspective, technology and human values, resource utilization and the American character, and contemporary moral problems.

Formidable stuff for many 17- and 18-year-olds.

“That was always a source of difficulty, that the ambitions of those courses could be achieved with a population that wasn't ready to deal with them,” said Professor Charles Matter, reflecting years later on his experiences as head of the USP unit from 1976 to 1978. “The courses were very value-oriented, very participatory.

“A third of the entering students loved the courses, a third sort of drifted through the program, and a third vigorously hated it. We had already begun to realize that there were problems and to talk about ways to change. Then the Logan-Murphy report blew everything out of the water—although I think we had already gone too far down the slide at that point, in terms of student resistance.”

Scrutiny of the program took on a sharper focus with a “special study commission on liberal education” headed by Professor Richard Sherrell. The commission report in January 1977 brought no immediate changes, but it fueled a debate that would continue through memos and position papers, in open forums and Faculty Senate meetings almost to the end of the calendar year. Final approval of a significantly new all-university requirement of 30 credits—intended to “more effectively attain the goals of the current distribution/USP programs”—came at the Faculty Senate meeting of Nov. 30, 1977. The new structure was largely the work of Professor Forrest Armstrong, associate dean of academic affairs, and Dean George Rupp, on the job five months in the academic affairs office.