Chapter Four: 1970–1971

“When we arrived, it was more promise than performance, because the program in place was no different in 1968 than in the years before that. There was a lot of talk, and people were using new words; in reality, though, my freshman year was what a student would have had at any UW Center. But it started to change, and it started to change pretty fast.”

— Judge Patrick Madden, Class of 1971, in a 1991 interview

Pat Madden was one of the pioneers: the first group of students to enroll after UW-Green Bay took control of the university centers in Northeastern Wisconsin. Encouraged by Donald Makuen, the energetic director of student affairs, Madden plunged into activities of the four-campus United Student Government, which included representative members of the student organization at each center. At the same time Madden tested the concept of “student power” on his own campus. After gaining student government approval of a resolution to silence the bells that signaled the end of 50-minute classes, he approached the main office secretary and asked to have the bells turned off.

“She went over to the panel and pulled the switch,” he recalled. “And that was it. That's when I realized that students were really going to be given a voice in student affairs.” Later, as editor of the student newspaper, Madden struck another symbolic blow for the new order. For years the Green Bay Center weekly had been published as The Bay Badger —“as though we were a small-town version of Madison.” Madden, who also viewed as an “affront” a campus pennant depicting a badger on water skis, decided to act. Between issues, with the approval of his staff, the editor rechristened the paper The Fourth Estate . And such it remained.

The opening of the new campus in 1969 was “like Christmas” for Madden and his friends.

“I'd been in, on or around every one of the foundations and structures of those buildings as they were put up,” Madden recalled. “It was as though we had a stake in every one of them. We'd go out and visit them like they were friends.”

That “campus of mud and promise” Madden remembers from his first year in the new location soon displayed at its center the skeleton of an immense building to house the library. Before winter was over visitors could also check the progress of a student housing complex, a private development rising northeast of the campus core. As the academic year ended, the developer announced that nine apartment buildings would be ready to occupy by fall. Providing quarters for 567 students, the project was intended to be the first phase of a two-part building program that would provide housing for 1,500 by the beginning of 1971-72. The student services staff scrambled to get a brochure printed and mailed to prospective residents, and the builder furnished a model unit for visitors to inspect during a midsummer open house. Sixty students applied for positions as resource students in the new residences; Madden was among the nine to be chosen, one for each building. Student services counselors provided training for the group at a summer workshop.

The summer also brought a kind of farewell party for longtime members of the Shorewood Country Club. Once a schedule was set for construction of the next academic buildings, Weidner invited Shorewood golfers to an outing at the future site of the Creative Communication complex. Even as workers moved trees and staked out fairways for a new nine-hole layout, 130 club members and guests took a final swing over the 18-hole course.

The Library Learning Center was taking shape in fall 1970. It would later be renamed the David A. Cofrin Library in fall 1990.

That “campus of mud and promise” Madden remembers from his first year in the new location soon displayed at its center the skeleton of an immense building to house the library. Before winter was over visitors could also check the progress of a student housing complex, a private development rising northeast of the campus core. As the academic year ended, the developer announced that nine apartment buildings would be ready to occupy by fall. Providing quarters for 567 students, the project was intended to be the first phase of a two-part building program that would provide housing for 1,500 by the beginning of 1971-72. The student services staff scrambled to get a brochure printed and mailed to prospective residents, and the builder furnished a model unit for visitors to inspect during a midsummer open house. Sixty students applied for positions as resource students in the new residences; Madden was among the nine to be chosen, one for each building. Student services counselors provided training for the group at a summer workshop.

The summer also brought a kind of farewell party for longtime members of the Shorewood Country Club. Once a schedule was set for construction of the next academic buildings, Weidner invited Shorewood golfers to an outing at the future site of the Creative Communication complex. Even as workers moved trees and staked out fairways for a new nine-hole layout, 130 club members and guests took a final swing over the 18-hole course.

Students and prospective students, meanwhile, struggled to adapt to new concepts and unfamiliar language in the curriculum. Interdisciplinary majors, called concentrations, were offered through four colleges, each organized around an aspect of the human environment. Students were encouraged to add in-depth study in a discipline (“option”) or in a professional program (“collateral”) available through the School of Professional Studies. All-university requirements were set forth as a four-year, 24-credit series of liberal education seminars, plus distribution courses in all four colleges and appropriate “tool” subjects: foreign language, studio art, data processing and mathematics.

Madden, like many of the early students, thrived on the innovations. But others who were puzzled or skeptical had also enrolled at the University, eager to complete a bachelor's degree without leaving the area. Enrollment at Green Bay as the 1970-71 year began stood at 2,954—a gain of almost 50 percent over the previous year. Each of the three two-year campuses, however, experienced a drop in enrollment. Weidner blamed the decline on increases in tuition and fees: “They have priced UW-Green Bay out of the market for part-time and special students,” he commented.

Faculty members, most of them educated in disciplinary specialties, faced their own challenges: designing courses within a new framework, learning the techniques of team teaching, adapting to makeshift facilities and inadequate equipment—and, in some cases, teaching classes at more than one campus.

By now, 324 men and women were members of the geographically integrated faculty and academic staff, and the University administration took pains to nurture a sense of institutional identity. Professors from all four locations served on faculty committees. National academic conferences and symposia, although staged at Green Bay, drew leadership from each campus. Library and instructional media materials traveled by truck between campuses on an almost daily schedule. And in October 1970 the University made higher education history in the state by inaugurating a closed-circuit television hook-up to Marinette. “Man and His Social Environment,” beamed from a studio on the Green Bay campus, became the first course taught in Wisconsin via live television. Seven instructors shared the task of instruction to a total of 800 students at the four locations. Students in the studio at Green Bay were connected to Marinette classmates by television; those at the Fox Valley and Manitowoc campuses participated by means of videotaped lectures and a telephone conference line.

United Student Government leaders also worked to integrate the university's scattered sites. Students from all four campuses nominated faculty members for a “teacher of the year” award sponsored by Standard Oil of Indiana. Students mingled at all-university dances and intercampus soccer games, and traveled and studied together in Europe during the January interim.

At the same time, in Green Bay, Weidner and his associates promoted activities to win community awareness and acceptance of the University.

Varsity soccer stars conducted free summer soccer clinics for boys and girls in Green Bay parks. Weidner encouraged biking families to exercise their wheels on campus walks and roadways. He personally played host to Green Bay city police and Brown County police officers at a golf outing on the Shorewood links. Dean Rollin Posey of the School of Professional Studies welcomed more than a hundred business leaders to a get-acquainted session focused on the UW-Green Bay business program. Faculty members recruited community lecturers who could bring local perspectives to the classroom. And Weidner's community advisory committees continued to meet regularly with University representatives to exchange ideas on issues ranging from curriculum and site planning to student health and public relations.

Two decades after graduating, Madden looked back on his years at the University as “a brief Camelot period,” when students and staff alike were caught up in the excitement of burgeoning growth and almost unbelievable success. But the speed of development produced growing pains, too.

The administrative structure in place as the campus opened lasted less than a year. Two weeks after the first commencement in May 1970, the regents accepted the resignations of Ronald Nettell, executive director of business and finance services, and two academic deans: Frederick Sargent of the College of Environmental Sciences and Edward Storey of the College of Creative Communication. All three had accepted positions elsewhere. In a “streamlining and realignment” of the administration that followed, Weidner replaced the four deans with a single dean of the colleges, an associate dean, and an assistant dean for each college.

Named to the “super dean” post was John Beaton, dean of the College of Human Biology. Bela Baker was appointed associate dean. Working with Beaton as assistant deans of the colleges would be four faculty members: James Clifton, Community Sciences; Coryl Crandall, Creative Communication; Alexander Doberenz, Human Biology; and Thomas McIntosh, Environmental Sciences. Eugene Hartley, dean of the College of Community Sciences, was appointed to the new post of dean for educational development.

Under the new structure, all concentration heads and assistant deans would report directly to Beaton. Associate Dean Baker would oversee programs in the disciplines and all-university studies. The School of Professional Studies, under Dean Rollin Posey, would continue to offer professional and pre-professional programs to supplement majors in the colleges. The administrative changes, Weidner said, reflected “a consensus of comment on how the University should implement the second phase of development of the academic plan.” Providing a single dean would also eliminate the possibility of too much autonomy for each college, Weidner argued.

Before the beginning of the 1970-71 academic year, Donald Makuen, too, had resigned. His successor as assistant chancellor for student services was Donald F. Harden, assistant dean and secretary of the faculty at Lyman Briggs College of Michigan State University.

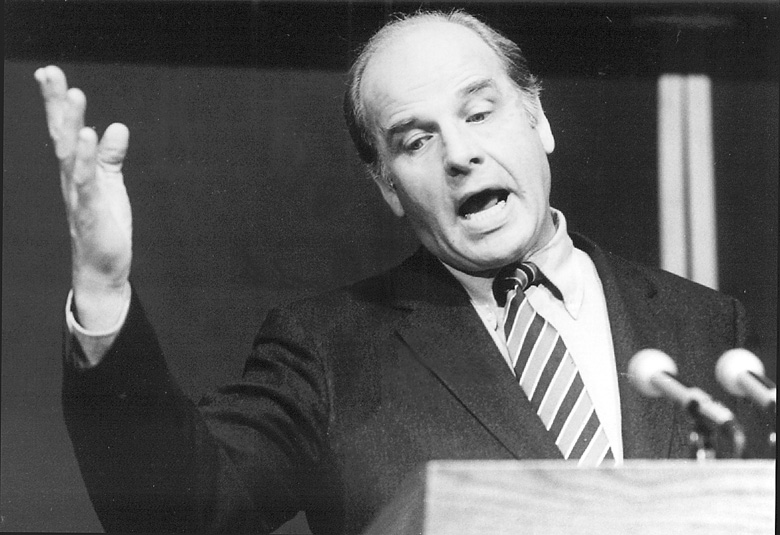

In Madison, meanwhile, UW-Green Bay lost a friend and advocate with the departure of Fred Harvey Harrington from the president's office. For many months Harrington had been a target of mounting criticism over his handling of student unrest. The bombing in August 1970 of the Mathematics Research Center on the Madison campus, resulting in the death of a scientist, was the final blow. Harrington resigned the following October and returned to the faculty. A month later, amid public demands for lower taxes and curbs on state spending, the Democrats took over the Statehouse.

The election of Patrick Lucey as governor would eventually set in motion a period of upheaval for higher education all over the state, and especially for the new institutions at Green Bay and Kenosha. For the present, though, the outlook remained favorable. The UW-Green Bay share of the state's first billion-dollar budget for higher education—which reflected a 35 percent increase in UW funding through state taxes—included almost $125,000 in special start-up funds to increase the custodial staff, expand the registrar's office and establish a safety program.

But fiscal clouds were gathering fast. The CCHE had already recommended termination of future start-up status for the two new campuses. The Legislature had trimmed UW-Green Bay building funds for the 1971-73 biennium from a requested $11.25 million to $7 million, once again deleting a physical education building. Yet Weidner, with good reason, remained optimistic about his operating budget. According to the funding formula in place, campus enrollments above official projections would be rewarded with additional funds. As long as the University continued to grow, it appeared that state tax dollars would be available to meet the cost of educating additional students.

Even as inflation soared and the national economy sputtered during Madden's final year, UW-Green Bay continued to prosper, riding high on a wave of environmental concern.

The Library Learning Center was taking shape in fall 1970. It would later be renamed the David A. Cofrin Library in fall 1990.

“These days everyone claims to be an ecologist,” commented a Milwaukee Journal writer, reporting on the University's first national conference on environmental education. The meeting attracted teachers from 21 states. Prominent scientists and social scientists flocked to the campus for winter conferences on population growth and the ecology of human living environments. Gov. Patrick Lucey, in office 22 days, appointed faculty biologist Robert Cook to a new task force on natural resources and environmental protection. A week later, at the urging of the United Student Government, Lucey declared April to be Wisconsin Environmental Action Month. U.S. Sen. Gaylord Nelson came to town to speak on “Wisdom in Making Environmental Decisions.” He was the first lecturer in a series that would include Harvard biochemist George Wald, Clark Kerr of the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, and Stewart Udall, who had been secretary of the interior under President John Kennedy. In February, students and faculty members walked house to house to share tips on protecting the environment. They presented seminars for manufacturers and skits for high school assemblies, and organized a citywide campaign to collect bottles for recycling. Bins and barrels installed on the main campus drive were soon joined by containers at other locations around Green Bay. In April, both Lucey and Nelson returned to the campus to speak at an Earth Week symposium on environmental quality and social responsibility. Back in Madison, the governor introduced a package of environment-related legislation and urged collegians to join him in the fight against pollution.

From the day the campus opened, the environmental focus of the academic program had attracted attention in newspapers and magazines across the country. But no single event would so firmly fix the image of the new University, for good or ill, as the publication of a 5,000-word article in the February 1971 issue of Harper's magazine. “Survival U. is alive and burgeoning in Green Bay, Wisconsin,” declared contributing editor John Fischer. It was, he wrote, the institution of higher education he had envisioned earlier for readers of his monthly “Easy Chair” column: a university “where all work would be focused on a single unifying idea, the study of human ecology and the building of an environment in which our species might be able to survive.” After visiting the campus in 1970, Fischer told his readers, “I came away persuaded that it is the most exciting and promising educational experiment that I have found anywhere.” He praised the UW-Green Bay program as “light-years away from anything ever tried before in Wisconsin or elsewhere. ... a truly radical innovation, not only in purpose but in its internal structure and methods of teaching.”

The piece was reprinted as a full-page feature in the Green Bay Press-Gazette ; it spawned other articles in publications from the Capital Times in Madison to the Cape Times in South Africa. When Newsweek dubbed the campus “Ecology U,” the name stuck.

Inquiries about the University flooded in from the East Coast and from overseas. Applications soared, while support of the higher education enterprise in Wisconsin steadily deteriorated in an austerity program ordered by Lucey soon after he took office. Faced with mounting inflation and a worsening economy, the new governor called for reductions in controllable costs in all state departments. John Weaver, new president of the UW System, responded with a freeze on hiring of academic and classified staff for the remainder of the fiscal year. Offers of employment for the following year were likewise put on hold, and previous restrictions on out-of-state travel were extended. A later directive on hiring for 1971-72 cut back new hires to 80 percent of previously authorized positions.

But the proposal that would permanently change higher education in Wisconsin was yet to come. On Feb. 25, as part of his budget message to the 1971 Legislature, Lucey formally recommended the move he had promised taxpayers during his campaign: merger of the state's two systems of higher education. The nine schools of the Wisconsin State University System would be merged into the University of Wisconsin, and the two governing boards combined into one. Related budget proposals were spelled out a few days later. Undergraduate funding for UW schools would be cut by $6.8 million to bring teaching costs in line with those of the WSU campuses; funds for graduate programs would be trimmed by $2.5 million.

Weidner's reaction was predictable. The governor's budget “deserts undergraduate education rather than supports it,” Weidner protested. Not only would the Green Bay complex be expected to absorb many more students while its base budget suffered $1.1 million in direct cuts and $2 million indirectly; the governor's budget also provided no funds for staffing, equipping and operating the Library-Learning Center, then under construction.

In a statement expressing his “deep concern,” Weidner predicted “a sterile homogenization and sameness for all 13 undergraduate degree-granting campuses” instead of encouragement of innovation and distinctiveness.

“Just at a time when the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay is receiving international recognition for its creative innovation in undergraduate education, the budget cuts would eliminate all start-up money for this new institution, would cut its budget base, and would add support for new students only below the University of Wisconsin average,” Weidner declared in a prepared statement. “Not only is there no recognition of the outstanding accomplishments of the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, but there is no consideration of the fact that a new institution inevitably has special development costs in its early years.”

In mid-May, after meeting with President Weaver, Lucey relented. Deciding that more time and study were needed to implement the principle of equal funding for equal programs in the two systems, he recommended that two-thirds of the earlier cuts be restored. The proposal for merger, however, remained—setting the stage for a political fight that would delay passage of a budget bill more than three months into the new fiscal year.