Chapter Fourteen: 1981—1982

“A lot of what went wrong in those early years certainly resulted from things beyond our control: the budget went haywire, merger came along. But a lot of it was self inflicted. We did so little to endear ourselves to the people of this region, including the students. Once we got that turned around, the University began to grow.” - Vice Chancellor William Kuepper in a 1991 interview

By the beginning of the 1981-82 year it was obvious that the trend of declining enrollment had been reversed.

What began as a modest recovery in undergraduate head count two years earlier had improved to a 24 percent increase over a four-year period. In fall 1981 each class showed substantial gains, with the largest increases tallied at the head of the “pipeline,” in freshmen and sophomores. Most encouraging of all, the FTE count, after six years of stagnation, had surpassed the previous high of 1974-75.

Fall enrollment stood at 4,536, not counting Extended Degree students. The student body was also the most diverse in UW-Green Bay history, drawn from 65 of the state's 72 counties and 30 other states, Maine to California. An international student community of 125 from 28 countries included 42 collegians from Malaysia. But the good news of enrollment brought its own down side: Two hundred students had to be turned away because of closed sections in courses they wanted or a lack of campus housing. In the first year of University ownership and operation, the University Village Apartments were filled to capacity.

The University's strategies were showing results. But athletic success, the opening of campus housing, and favorable press were only a few of the forces at work.

By 1981, with an alumni count over 4,700, the word was getting out about the availability at UW-Green Bay of career-oriented majors as well as liberal arts programs. About opportunities for research, internships, work and foreign travel as well as classroom study. About supportive faculty and staff. About graduates who were finding good jobs despite a depressed economy.

The completion of major highway projects, in the works for years, made the campus newly accessible to all of Northeastern Wisconsin. Weidner himself was master of ceremonies at the opening of the Tower Drive bridge in October 1980. Five years in the planning, the 120-foot-high span provided a time-saving link to the city's west side as well as to the Fox River valley via US Highway 41. A year later Associate Chancellor Harden cut the ribbon on the final stretch of Interstate 43 south. Now the campus was also connected by an express route to Milwaukee and communities along the Lake Michigan shore.

Within the University, meanwhile, staff members were charting new routes of accessibility to learning.

The Extended Degree program, with authority and funding to double its enrollment, recruited a record 195 students. The admissions office opened a new counseling service specifically for adults who were not recent high school graduates. When the outreach staff organized a “first step seminar,” 65 prospective students showed up to share their hopes and anxieties about starting college with other adults already on the way to a degree. Seminar participants ranged in age from the early 20s to over 60.

Students from eight public high schools came to the campus to match wits in the first University-sponsored academic competition. Questions in the categories of mathematics, science, social studies and language arts were fashioned by UW-Green Bay faculty members, who also served as judges. The winning teams carried home trophies provided by the Founders Association. Growth was recorded, too, at the Elderhostel end of the age spectrum. The popular summer program for the 60-plus crowd expanded to two one-week sessions offering, among other courses, studies labeled Sex and Society and Science and Controversy.

Equally energetic efforts moved teaching and learning off the campus and into the community.

In an outreach “learn and shop” program, faculty members met students in classrooms at the Port Plaza Mall downtown. Three-credit, freshman-level courses—like Introduction to Sociology, Women and the Law, and You and Your Food—were staples of the curriculum. The University also expanded its geographical reach to UW centers in the region. Upper-level courses in marketing and labor legislation opened for evening enrollment in Manitowoc. Marinette-area teachers could sign up for an education course worth two graduate credits from UW-Green Bay or from the co-sponsoring institution, Northern Michigan University. Classes were held at the UW Center in Marinette. While classroom-based students sampled university fare “live,” stay-at-homes could learn about masters and masterpieces of music in 30 lessons taped for radio broadcast by Professor Arthur Cohrs.

Sometimes the lecture hall was a restaurant and the course a one-hour talk on alternative energy, Middle East politics, or climate change, as faculty members shared information and insights at luncheon meetings of service clubs. Churches, public schools, nursing homes, and corporate conference rooms provided other settings for faculty participants in the outreach speakers bureau. Presentations were as varied as groups requesting them: from Richard Jansen's human relations session for bank trainees to Kumar Kangayappan's introduction to India, prepared for sixth graders at Bayview Middle School. Before the academic year ended, volunteers from the University community would fill 90 speaking engagements before members of 60 different organizations.

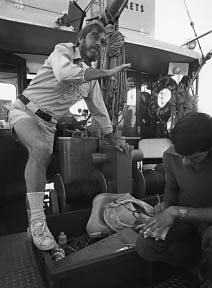

Bud Harris on board the Aquarius

For three days on board the research vessel Aquarius, anchored at the Holiday Inn, Hallett “Bud” Harris and James Wiersma educated visitors about the work of the UW-Green Bay Sea Grant program. Coached by the two faculty members, would-be researchers of all ages helped to take samples of bottom sediments, check water temperatures, test for light penetration and dissolved oxygen content, and assess the Fox River population of plankton. The Knapsack Storytellers of the University League offered free storytelling workshops at the Port Plaza Mall. Sessions targeted the same goal as that of the group's eagerly awaited appearances in classrooms and libraries: to encourage a love of reading. And faculty poet Peter Stambler took to the road on a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council. In libraries all over Wisconsin, he presented readings from Wilderness Fires, his prize-winning collection of dramatic monologues based on accounts of the Peshtigo fire of 1871.

There was no question, by now, that the University's relationship with the community had “turned around.” Couples who ventured to the campus initially to attend a band concert, fulfilling a parental duty, would bring other family members back for a soccer game. Sports fans already hooked on varsity basketball at the arena discovered the excitement generated on the sports center floor by the Phoenix women, perennial 20-game winners.

The campus became a popular destination. Theater buffs could attend an elegantly staged midwinter musical— Brigadoon one season, Mikado the next—a prize-winning play like Elephant Man, on national tour, or a family show of mime and magic. Music lovers could choose a professional revue of Fats Waller favorites or the Vienna Choir Boys. A campus production of Mozart's Magic Flute brought community singers and student musicians together under the baton of Miroslav Pansky, Green Bay Symphony conductor. The first locally produced opera in Green Bay history, it quickly sold out five performances.

In growing numbers, visitors headed to the campus for spring commencement, now an outdoor celebration in the best academic tradition. Some came to see foreign films in the Christie Theatre, others to sample the foods and scenery of foreign countries at dinner-lecture programs. They also came to take a look at famous faces. The presidential election year brought Rosalyn Carter and Ted Kennedy to the campus in April, while George Bush stopped at St. Norbert College. Ralph Nader followed in September.

And 20,000 men, women and children arrived, all in two days, for Bayfest '81, a fundraiser for intercollegiate athletics.

The Phoenix men, 23-9 during 1980-81, their final Division II season, had taken the North Central Regional for the third time in four years and advanced to the final four in the national tournament. Ahead were the uncharted waters—and burgeoning expenses—of Division I. What better time for a community party that could also raise money for the athletic program? And what better place than the grassy expanse of the Phoenix soccer field?

Bayfest director Tim Quigley enlisted the help of campus and community organizations to mount what he promised would be “the greatest summer entertainment north of Milwaukee's Summerfest.” The mid-July weather turned torrid. Capricious winds cancelled one hot-air balloon race on Saturday; early morning fog wiped out another on Sunday. But a celebrity dunk tank, flea market, bluegrass festival, antique car show, midway carnival rides and sales of ethnic food specialties proceeded on schedule. And 39 non-profit groups besides the sports program made some money.

“I think we're onto something,” Quigley told a News-Chronicle reporter.

Thousands converge on campus for Bayfest each year.

Community response to Bayfest, steadily improving enrollment, new roads to the campus, major gifts for research and national honors for the Center for Television Production contributed to the “cheery” news reported by Weidner at yet another beginning-of-the-year breakfast in September 1981. But most of his annual address focused on “a dreary, unhappy subject, namely finance.”

While adding 1,100 students over four years, he told his audience—“the equivalent of a Lawrence University or a Beloit College”—UW-Green Bay received no additional support and in fact suffered a budget reduction. Excluding annual salary adjustments, the cuts over three years amounted to $600,000 and 26 positions. And no funds had come to offset inflation, a cumulative 41 percent over four years. Weidner ticked off the results:

- An 18 percent decrease in employees.

- A decline of 65 percent in library book purchases and 45 percent in periodicals subscriptions.

- A mounting tally of closed courses each semester.

- Significant cuts in routine maintenance, like window washing.

There was no alternative, Weidner declared, but to support a tuition surcharge for the second semester, as proposed by the regents. The added amount would be $30 for some campuses and $23 for others, including Green Bay.

“I have spent all my life trying to keep tuition down,” Weidner said. “But when the choice is either a quality education supported by some additional fee, or a steady erosion of quality that comes with keeping tuition down, I have to make the first choice.”

Almost five years would pass before the regents formally adopted an enrollment management policy. But in the fall of 1981, as Weidner approached the 15th anniversary of his appointment as chancellor, a chapter in the history of the UW System was quietly closing. And the long, often heated debate on access versus quality in public higher education was slowly moving to center stage on the Wisconsin political scene.